In the rugged hills and rural towns of Northern California, a showdown was brewing. Pitting peace-loving hippie ganja growers against the full force of the Feds, the ugliness of prohibition plunged the region into a war over homegrown cannabis that lasted throughout the 1980s and beyond.

Focused on seizing cash and valuables while destroying harvests and imprisoning growers, DEA agents flooded the Emerald Triangle in an attempt to infiltrate the community.

The CAMP Years

As the price of Emerald Triangle cannabis grew to $4,000/lb., farmers began to be motivated by profit, not just supplying personal stashes to friends and family. Suddenly the illicit cash that financed a thriving local economy, schools, and volunteer fire departments were threatened by the government’s policy of prohibition. But the riskier things got, the more the prices went up, motivating growers to do things that got them into trouble.

In 1983, the Campaign Against Marijuana Planting—also known as CAMP—was formed. Composed of local, state, and federal agencies, this multi-agency task force was overseen by the California Department of Justice. The goal was—and still is today—explicitly to eradicate illegal cannabis cultivation and trafficking in California.

For people living in Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity counties, that meant constant disruptions to their peaceful way of life. Helicopters flew overhead daily looking to spot illegal grows, many of which were burnt to the ground by Federal agents.

During the prime summer and fall months for cultivation (July through October) there were ground crews and helicopters invading the forests in search of cannabis grows. Hoping to create a deterrent, CAMP wanted farmers to give up and stop growing, but it had a paradoxical effect of only making the illicit harvests more valuable, and attracting more determined farmers who were increasingly accustomed to criminality.

CAMP involvement drove growers further into the woods, forcing them to get more creative in how they hid their plants. The community banded together to repel the outsiders and narcs, with radio bulletins warning farmers of oncoming law enforcement caravans and helicopters. Stories abound of CAMP officers being sabotaged by hotel employees rubbing poison ivy on the bed linens, and diner cooks spitting in their food.

A Hard Life for Cannabis Farmers

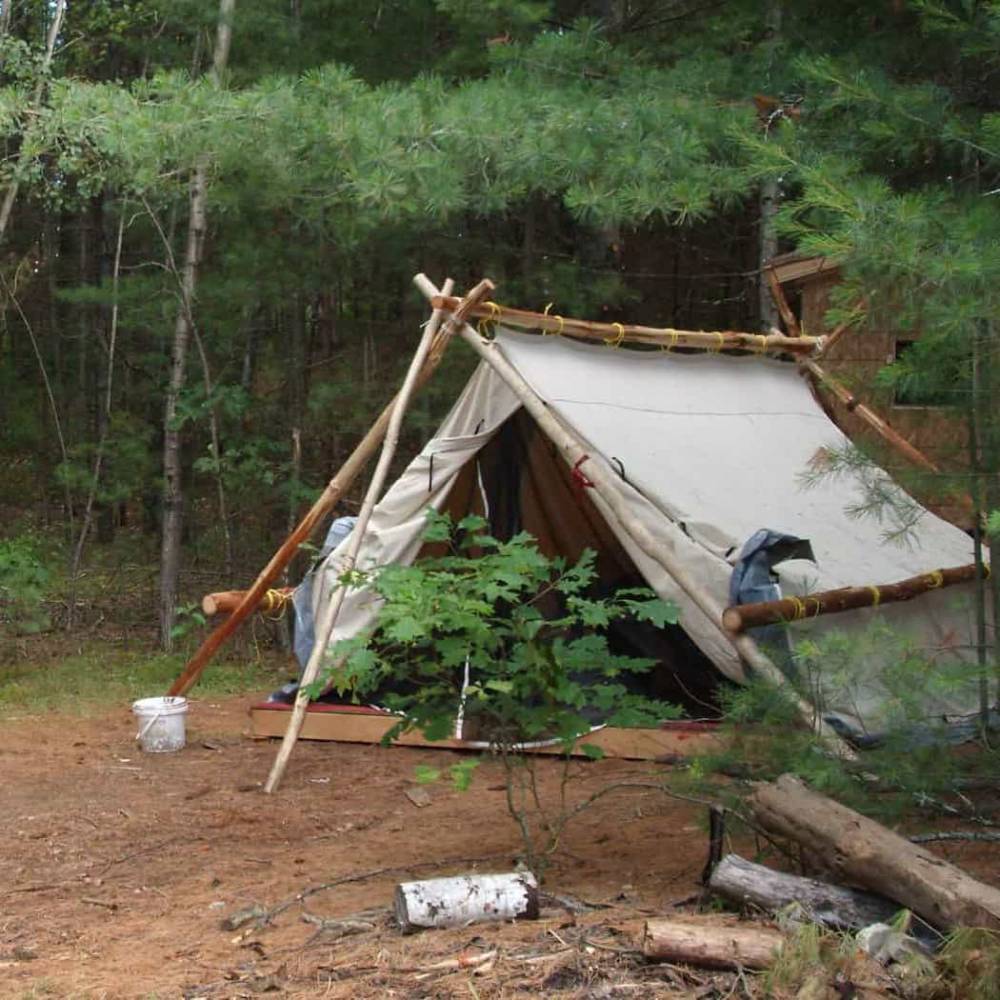

Today, the origin of the Emerald Triangle and the CAMP battles are often romanticized, but for those who lived through it, the situation was traumatizing, creating citizens with a life-long distrust of the government. Farmers couldn’t risk being seen coming and going from their grow sites all the time, so many chose to live out of tents nearby. They would eat cheap and easy-to-make meals like beans and rice. It was a lifestyle comparable to the hardscrabble miners who flocked to the Sierras, trying to strike gold in the 1800s.

Growers would hide their cannabis crops underbrush and leaves of Manzanita bushes, covering their tracks on their way out. Irrigation lines were a complicated process too, as they needed to be hidden from heat-detecting cameras on planes being flown above searching specifically for them.

Most of the time, proper soil and fertilizer weren’t available either. Local sheriffs and DEA agents would stakeout local nurseries, in hopes of following you to your illegal grow.

Instead, farmers would make their own soil from forest duff and chicken manure. Sometimes, their own urine was needed to enrich nitrogen levels. Though, others eventually chose to grow nitrogen-rich legumes in the same soil as the cannabis.

Increasing Paranoia Isolates the Community

The illegal activity in the Emerald Triangle and the heavy-handed government efforts to end it didn’t go unnoticed by the rest of the world. Journalists would come to Humboldt county in hopes of being able to tell "the true story" of The Emerald Triangle, but not a single soul would talk to them, other than law enforcement.

The reason? Everyone was suspicious of everyone. If you weren’t a known local, you couldn’t be trusted. It wasn’t worth the risk of losing your loved ones and your economic security just to talk to reporters.

The media coverage only reflected the perspectives of local law enforcement, while the peaceful, eco-friendly values of the homesteaders weren’t communicated to the public.

Painted as a lawless place, the Emerald Triangle was depicted as full of renegade Vietnam veterans forming militias in the woods, booby-trapping their illegal gardens. The community was vilified as a place where mafia-style criminals and gangs ruled supreme, not as a rural region where peaceful farmers and their families sought a better way of life.

The 1980s were a rough time for the people of Humboldt and Northern California. Especially for those farmers who never gave into law enforcement demands. If it weren’t for their perseverance, cannabis culture would be much different today.

"It was a war on the people, not a war on the plant," Pat Andrews of Ice Box Flat Farms told Wick and Mortar.

Telling These Stories Keeps the Culture Alive

If we don't tell these stories they will be forgotten. The world is changing, and cannabis is becoming just another consumer packaged goods. We can’t let the incredible culture and the history of this plant and these people be disrespected.

If these farmers had simply given up when CAMP started burning their crops to the ground, cannabis could still be illegal today.

To learn more about the history of cannabis prohibition in California, keep an eye out for Part 3: The Medical Marijuana Movement. Learn how activists fought for our right to use cannabis as a medicine. And how the medical use of cannabis foretold the beginning of the end of prohibition.

In the meantime, don’t forget legalization is still an ongoing fight. And it's not over when initial laws are passed. Support this struggle to end prohibition and reverse the effects of the War on Drugs by following Farmer and the Felon Cannabis Co. and The Last Prisoner Project on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter!